The 22nd of September marks World Rhino Day.

Close to 10,000 rhinos have been lost to poaching in the last decade alone. The peak of poaching was just five years ago in 2015 when 1,349 rhino were recorded as poached.

This demand for rhino horn is driven by the Far East where the horn is believed to have medicinal benefits and is used in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). In places like Vietnam, rhino horn is considered a status symbol. There have been reports of horn being crushed and added to drinks at parties, being used as a hangover tonic, or as a miracle cure for any number of diseases. In reality, rhino horn has not been proven to hold any medicinal benefit. This tough and dense material is made largely of a protein called keratin, just like our hair and nails. The horn, of course, belongs on the rhino where it is used for digging, defence and for posturing.

Various techniques have been trialled including dehorning, poisoning and dyeing rhino horn. A horn dyeing trial did take place in Sabi Sands, South Africa some years ago but was not successful: the dye was found to disappear within about a month; dye applied only on the surface of the tusk/horn could be easily sanded off; dye made it difficult for the animal to camouflage itself making it even more obvious to poachers; dye did not deter poachers in Sabi Sands & animals were lost. Injections of poison have also been tested on rhino horn but were not discovered to be a good deterrent – horn is non-porous so the poison does not diffuse. De-horning has been conducted on a wider scale, for example in Namibia, but poachers have still attacked & killed de-horned rhinos, for instance in the Save Valley in Zimbabwe. A dehorned rhino has a slightly better chance of survival, yes, but sadly poachers will still kill them if they are the only option as the remaining stub of horn still has some value.

Poaching isn’t the only threat to rhino – habitat loss is a significant factor in their decline, particularly for the Asian species of rhino.

Know your Rhino

There are five species of rhino. Two in Africa (Black and White), and three in Asia (Sumatran, Javan and Greater One Horned). Three of the five species are classed as Critically Endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Javan rhinos are browsers living in tropical rainforest almost exclusively within Indonesia’s Ujung Kulon National Park – a precious small population of 74 is protected by armed guards. Females do not have a prominent horn and give birth to a single calf every 2-3 years. The biggest threat to the Javan rhino is its small population which leads to inter-breeding and loss of genetic strength and diversity. Although the population rallied from a low of just 30 individuals in the 1960s, reproduction has slowed significantly in recent years.

Sumatran rhino face a similar challenge existing only in fragmented populations. Their range has greatly reduced over the years to just Indonesia (Sumatra and Borneo) – they used to be found all over Asia as far as Bhutan. Climate change and widespread deforestation are the main reasons for their decline. Fragmentation prevents rhino from meeting and breeding. Just two calves have been born in captivity in the last 15 years. The population is estimated to be less than 80. Sumatran rhino are the smallest of the five species and also known as the Woolly Rhino due to their reddish brown hair.

Black rhino (above) are also Critically Endangered. They are the smaller of the two African species living in sub-Saharan Africa. They are browsers and can be found on grassland and savanna using their characteristic hooked lip to snap leaves and fruit from trees and bushes. Their numbers hover around 5,300, having more than doubled in the last two decades thanks to concerted conservation efforts. These efforts came too late for the Western Black Rhino, a subspecies declared extinct in 2011. The main threat to Black rhino is poaching. Black rhino have two horns which grow throughout their life and it is these which are targeted by poachers. One of the best places to see black rhino and learn about their conservation is Kenya. Nairobi National Park has the highest density of black rhino while Ol Pejeta, Solio and Lewa, all in Laikipia, offer excellent sightings of both black and white rhino and have extensive rhino conservation and protection programmes. In 2018 we funded a conservation canine, Drum, for Ol Pejeta. He is now part of the canine unit which helps to protect black and white rhino on the conservancy.

The Greater One Horned Rhino lives in India & Nepal and is classed Vulnerable by IUCN – the species recovery from 200 individuals following extensive hunting and harassment in the 1900s to around 3,500 today is a conservation success story. Eco-tourism has generated much needed funds for their protection in places like Chitwan and Kaziranga. Poaching is still a threat, as is habitat loss with much of the rhino’s ideal habitat under pressure from agriculture. One Horned Rhinos are semi aquatic and live on floodplains, in swamps and forest.

The White Rhino (above) is found in Africa with the majority of the species found in South Africa although thanks to translocations and breeding programmes their range is now increasing. They are the second largest land mammal and have impressive horns and a huge square lip which acts like a giant lawn mower, allowing them to methodically graze the savanna and grassland. The Southern White Rhino is the most populous rhino and is classed as Near Threatened. Southern Whites have bounced back from extinction and prove that conservation does work. There are around 19,000 today – many live on private conservancies with armed guards and anti-poaching units protecting them around the clock. As recently as the 1960s there were thought to be only around 100 remaining. As conservationists worked to protect the white rhino, poachers shifted their attention to the smaller black rhino which then declined by a staggering 60% to just 2500 individuals.

The White Rhino (above) is found in Africa with the majority of the species found in South Africa although thanks to translocations and breeding programmes their range is now increasing. They are the second largest land mammal and have impressive horns and a huge square lip which acts like a giant lawn mower, allowing them to methodically graze the savanna and grassland. The Southern White Rhino is the most populous rhino and is classed as Near Threatened. Southern Whites have bounced back from extinction and prove that conservation does work. There are around 19,000 today – many live on private conservancies with armed guards and anti-poaching units protecting them around the clock. As recently as the 1960s there were thought to be only around 100 remaining. As conservationists worked to protect the white rhino, poachers shifted their attention to the smaller black rhino which then declined by a staggering 60% to just 2500 individuals.

Northern Whites are on the brink of extinction with just two females, Najin and Fatu remaining at Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya after the loss of the last male of the species, Sudan in 2018. IVF research continues at Ol Pejeta and it was reported earlier this year that embryos had been successfully created by combining frozen sperm taken from male rhinos before they died with eggs harvested from the two females.

We are proud to have facilitated and funded the purchase and training of four rhino protection dogs to the following areas of Africa – these areas are known to have viable black rhino breeding populations – there are fewer than ten of these areas in Africa.

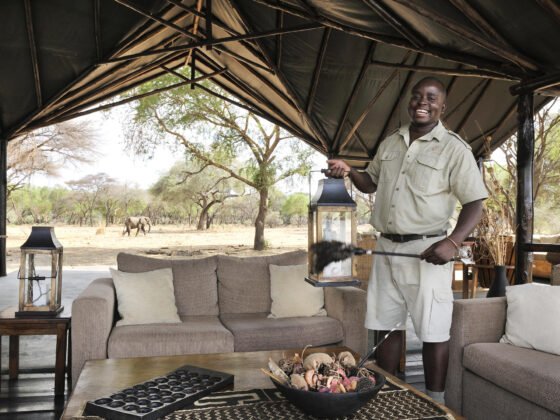

Savas and Primaa went to Botswana’s Okavango Delta; Drum went to Ol Pejeta Conservancy, Kenya; Vaala went to the Save Valley, Zimbabwe.

We remain committed to rhino conservation and working with our partners to secure a brighter future for rhino. If you’d like to support our work then please consider making a donation, or purchasing an artwork, or Tshirt in our online store. All profit goes to our Project Fund. Thank you.