When you think of kelp, you think of cold water and the famous forests of the North-west coast of America. But actually kelp forests are found along roughly one quarter of the world’s coastlines.

These dense underwater canopies are one of the world’s most biodiverse ecosytems, rivalling the rainforest, with thick strands of algae providing food and shelter for many species.

Brown algae needs to photosynthesize so kelp forests generally thrive in shallow water of between 15m and 40m. The optimum ocean temperature range, depending on species, is 5-20 degrees with die-back seen over 20 degrees.

Kelp, of which there are more than 100 species, can grow as much as two feet a day, given optimum conditions, providing an important carbon store and a complex habitat from sea floor to surface.

But studies have shown that kelp is being lost from our coastlines – whole forests disappeared along the coasts of Tasmania (2011) and California (2014) following marine heatwaves, when the ocean temperature exceeded 20 degrees. Norway, Australia and eatern regions of Canada have also seen huge losses.

Warming ocean currents, pollution, overharvesting and other human activities threaten kelp forests. For example, Chile has one of the biggest kelp harvests in the world but very little research has been done on the impact of harvesting, while monitoring and accurate reporting is lacking.

Restoration poses a range of challenges from finding the right site for different species of kelp to thrive, to the right substrate to grow the kelp succesfully, so discovery of new forests growing at different conditions is hugely important, particularly finding species which can survive at warmer ocean temperatures.

New research published in Marine Biology by the Charles Darwin Foundation’s Seamount Project in collaboration with a scientific team from the University of Malaga has discovered a vast tropical kelp forest on top of a seamount in the southern Galapagos islands.

A seamount is an underwater mountain as a result of volcanic activity.

Notably the seamount kelp is visibly bigger (twice the size) and differs in appearance from the coastal kelp species, Eisenia galapagensis documented in other parts of the Galapagos. In addition this new seamount kelp has been found growing at a far greater depth.

ROVs were used to explore the kelp forest at its greatest depth while scuba teams also documented the kelp and were able to take samples for analysis. This will determine taxonomy.

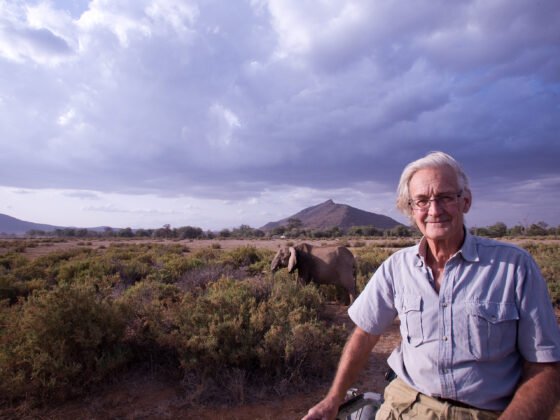

Image: University of Malaga and Charles Darwin Foundation