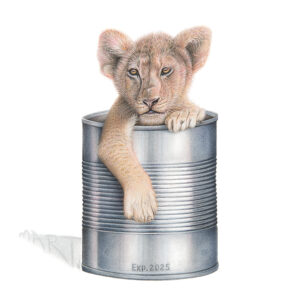

Could Soil Carbon replace Trophy Hunting?

When it comes to wildlife conservation, nothing quite gets people’s emotions charged like the issue of trophy hunting. Some view it as an inexpiable evil, whereas others say it is necessary to avoid greater suffering. Across Africa an area seven times the size of the United Kingdom is set aside for trophy hunting. In some instances part of the revenue generated from selling hunts is invested in wider community conservation, which helps sustain ecological equilibrium by incentivising local people to be less reliant on destructive practices like slash and burn agriculture. Were we to abolish trophy hunting tomorrow, we would need to come up with an alternative land use strategy that deters international poaching cartels and supports honest, but desperate, people. Otherwise a tsunami of habitat destruction is likely to wash away wildlife for good.

In spite of what some trophy hunting enthusiasts might have you believe, trophy hunting itself does not protect wildlife. What does is revenue generating forms of land use. It just so happens that in many cases trophy hunting is the preferred model, as it is viewed as the best case scenario in terms of cost versus reward. There is a popular saying in southern Africa, ‘if it pays, it stays’. Despite trophy hunting being involved in exporting dead animals out of Africa, the business pays, and therefore it stays.

My own view on trophy hunting is that it is an elitist anachronism from a bygone era when killing animals for fun didn’t garner the same outrage as it does today. I think that when it comes to trophy hunters, for the most part, wildlife conservation is a convenient justification for a game they enjoy playing, as opposed to a genuine desire. I feel that trophy hunting is damaging to the image of conservation and confusing for people who are new to the space. On the one hand you have a headline that reads ‘One in six species are at risk of extinction in Great Britain’; meanwhile Trevor from Melton Mowbray just shot a critically endangered black rhino to help protect the species from extinction. When Sir David Attenborough made a brief foray onto Instagram in 2020, he said that saving the planet is now a communications challenge. Optics matter, perhaps more than they ever have.

If what we want is a more respectful and less destructive relationship with the natural world, then we really ought to draw the line at killing animals for fun. As long as trophy hunters insist on sharing photos of themselves on the internet, grinning ear to ear and posing next to the lifeless carcass of the animal they just shot, you are never going to persuade people that ‘killing to conserve’ is an appropriate model, no matter how much science there is to back it up.

One of the biggest factors driving extinction is human made climate change. We are pumping carbon into the atmosphere at a rate that nature can’t adjust to, and it is negatively affecting entire ecosystems and the people and wildlife who live there. In addition to protecting wildlife and supporting local communities, any decisions about land use should also focus on mitigating the devastating effects of climate change. What many people don’t realise is that there is up to 4 times more carbon in the top one meter of soil on the planet than there is in the atmosphere, and it is in all of our best interests to keep it there.

In Zambia a social enterprise called BioCarbon Partners has established two carbon initiatives where income is generated by preventing annual carbon dioxide emissions of 1.4 million tons from deforestation. If the carbon stays, it pays. Credits are sold to clients looking to offset their greenhouse gas emissions, and the funds pay for the protection of nearly one million hectares of community forest. In 2020-2021 the Luangwa Valley Community Forests Project (LCFP) generated over USD $4 million in direct payments to 12 chiefdoms, outcompeting both trophy hunting and tourism in terms of revenue generated for communities.

LCFP is a REDD+ project, which stands for ‘Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation’. The ‘+’ refers to additional forest related activities that protect the climate. REDD+ projects are not without flaws, and some have been found to overestimate the levels of deforestation that would have occurred without them, making it difficult to quantity the actual value of the credits they offer.

While REDD+ projects are primarily concerned with avoiding the loss of carbon, soil carbon projects deal with actually removing it from the air and storing it in the ground. This process, known as ‘sequestering’, is achieved naturally by increasing the amount of decomposing plant material and microbes in the soil through strategies such as rotational grazing and fire management. If done properly, such practices can help turn previously degraded landscapes into healthy ecosystems that support wildlife populations and store carbon more effectively.

Many anti-hunting activists point to eco-tourism as a replacement for trophy hunting. ’Shoot it with a camera, not a gun’ is a well trodden phrase, but the rebuttal put forward by the pro-hunting fraternity is that it won’t work because, unlike trophy hunting, photographic tourism relies on accessible landscapes where wildlife viewing is made easier. This is not the case with soil carbon, making it a more viable alternative. Tear et al. 2001 identified the potential for serious revenue from soil carbon in all 198 protected areas where lions exist in Africa.

The issue of wildlife conservation is indeed complex and there is no perfect solution. Some will criticise carbon schemes as allowing greenwashing by companies, pointing to shoddy methodologies used for valuing credits. This feels a little defeatist to me. Our species has successfully landed spacecrafts on Mars, so surely there are people smart enough to come up with a working methodology? If not, can we maybe ask AI, because removing carbon from the atmosphere is clearly a good thing. Many African countries are amongst those worst hit by the climate crisis, whilst having had very little to do with causing it in the first place. Through carbon financing, land can deliver a cash return locally whilst also becoming more climate resilient, to the benefit of all of us. Wildlife conservation might finally be able to finance itself and not be so reliant on philanthropy, which only goes so far. If options like this are feasible, why would anyone nowadays even think of choosing trophy hunting?